The head of a state-backed panel tasked with finding ways for Israel to train more doctors has condemned the government’s recent decision to shutter three medical schools that cater to foreign students to make room for more locals, maintaining that the contentious and costly move was unnecessary .

Earlier this month, the Council for Higher Education announced it was shuttering American medical programs at Tel Aviv University, Ben Gurion University and the Technion in order to replace the 130 foreign students that study in them with Israelis, in light of a growing doctor shortage in the country.

But on Wednesday, Prof. Rafael Beyar, who led the council’s own committee to investigate ways to boost Israeli medical student numbers, told The Times of Israel that there were other ways to reach the goal.

“[The committee] put forward a detailed plan for how to accept 400 additional medical students for four-year programs. There was no need to close the foreign programs in order to accept those additional 400 [students],” said Beyar, who also recently wrote a letter to the council criticizing the decision to shutter the programs.

The State of Israel already has a shortage of doctors, particularly in farther-flung parts of the country, and the situation is expected to get far worse in the coming years in light of Israel’s aging population requiring greater medical care, as well as an expected wave of doctors set to retire.

The majority of doctors in Israel are currently forced to study abroad due to a critical lack of spots available at Israeli medical schools.

One of the major obstacles is expanding the amount of so-called “clinical spaces,” spots in hospitals and laboratories where medical students get hands-on experience.

The American programs allow foreign nationals to study in Israel but receive American degrees and perform their residencies in the United States. They have long been seen as a boon to the Israeli medical system, bringing in large amounts of money in tuition payments — foreign students pay more than 10 times as much as Israelis — as well as increasing Israel’s academic reputation internationally and creating an informal network of doctors in the United States with close ties to Israel.

Prof. Rafi Beyar, former director of Haifa’s Rambam Medical Center, on October 30, 2011. (Yossi Zamir/Flash90)

Beyar, the former director of Haifa’s Rambam Medical Center and former dean of the Technion’s medical school, stressed that the letter to the council represented his own personal opinion and not that of the committee.

Though he confirmed sending the letter to the council, he refrained from providing a copy of it, saying the full contents were “meant for the council and professional officials.”

A council spokesperson said she was not immediately aware of the letter but brushed off Beyar’s opposition. She stressed the magnitude of the problem facing the Israeli healthcare system and the obstacles in place that make it difficult to radically increase the number of medical students.

“It’s easy to throw out numbers like 400 extra spots, but there are practical considerations,” the spokesperson said. “Any time you make a decision there are going to be people who disagree with it.”

A 2017 report by the State Comptroller’s Office regarding Israeli medical schools also found that the shortage could be addressed in other ways, but that a lack of proper communication between the council and the Health Ministry prevented it.

“There are other, relatively simple solutions for adding clinical spaces in hospitals that have not been considered, but a lack of a comprehensive, systemic way of thinking prevents them from being added,” the comptroller wrote.

Beyar is not the only senior medical official to oppose the decision to shut the American programs.

Prof. Arnon Afek, acting director of Sheba Medical Center and a former director-general of the Health Ministry, railed against the move, calling it “unnecessary and wretched.”

“Yes, Israel needs to train its own doctors, and the current situation in which only 40% of doctors receive their degrees in Israel and the majority study abroad — that’s unreasonable and unconscionable,” he told The Times of Israel.

“But I don’t see a single reason to close the American programs,” said Afek, who previously led Tel Aviv University’s American program.

Then-director-general of the Health Ministry, Prof. Arnon Afek, speaks during a press conference announcing the new mental health reform presented by the Health Ministry in Jerusalem on July 1, 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

“It really hurts my heart,” he said. “It’s so hard to build something and so easy to destroy it.”

Afek, who has extensively investigated and written about Israel’s doctor shortage for academic journals for over a decade, said Israel needs to add some 800 new medical students each year in order to overcome the looming shortage. He maintained the goal was feasible, but only if the government allocates the necessary funds to address the issue.

“The claims about a lack of clinical spaces are nonsense. Nonsense! They didn’t even ask us, the heads of hospitals, about it,” he said. “I’m telling you there is absolutely, positively no problem to do this. Don’t get me wrong, it would require an investment of resources, but it’s like any investment, it’s an investment in the country. It’s an investment in our ability to treat our grandparents, our children.”

Afek principally advocates opening new medical schools in Israel. He is currently spearheading the effort to establish one at Reichman University in Herzliya, formerly known as the Interdisciplinary Center.

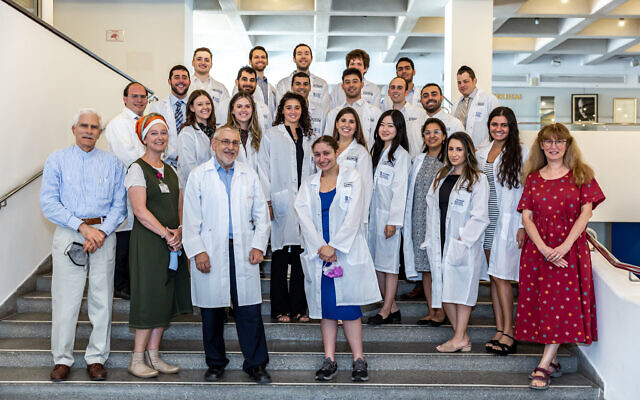

Graduates of the Technion’s American Medical School program pose for a photograph after receiving their white coats in 2021. (Technion)

The Council for Higher Education spokesperson claims that there was no other option but the closing of the American programs to increase the number of Israeli medical students beginning in the fall of 2023, with all of the alternatives being too expensive or too complicated to implement.

Asked how the government then planned to add the hundreds of new spots that are needed to address the shortage, the spokesperson said the issue was still being considered.

“This coming academic year, we increased the number of spots by 70. The following year, [by closing the American programs] we are adding another 130. I don’t know what will happen the following year. They are working on it,” she said.

Afek also questioned why the council didn’t at least first try some type of interim measure to entice students in the American programs eligible for citizenship to remain in Israel after graduation and thus increase the number of doctors in Israel.

Indeed, though a not insignificant number of alumni do indeed come back to Israel — including this reporter’s brother-in-law — the vast majority settle in the United States.

The Technion medical school building in Haifa is seen to the left of Rambam Medical Center. (CC BY David King, Flickr)

However, the decision to return to the US is often a financial one. Saddled with several hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt, even those graduates who plan to eventually move to Israel first seek more lucrative careers in the United States, where the salaries for doctors are far higher than in Israel.

The government plans to compensate the universities being forced to give up the higher tuitions they could charge foreign students. But Afek said the funds could have instead been offered to students in the American program in exchange for a requirement to practice medicine in Israel for a certain number of years.

“Why not offer instead to help pay their debts? So many of them want to stay in Israel,” Afek.

The council spokesperson rejected this solution as far-fetched, believing that not nearly enough foreign students would take up the offer.

‘Why make a committee?’

Afek also fumed over the fact the council’s decision, made in conjunction with the Health and Education ministries, was not in line with the recommendations of Beyar’s committee.

“Why would you make a committee if you’re just going to do what you want to do anyway,” he asked. “They didn’t check with anyone, they didn’t ask anyone, they just went ahead and did it.”

The council spokesperson said she could not comment on why the committee’s recommendations weren’t followed and referred The Times of Israel to the Education Ministry.

Education Minister Yifat Shasha-Biton did not respond as of publication.

Afek, who served as director-general of the Health Ministry from 2014 to 2015, described the shuttering of the American programs in favor of Israeli students as being not only a “Band-aid on a gunshot wound,” but one that comes at a considerable cost.

“This is a drop in the ocean that will only cause damage: to the image of Israel, to the reputation of Israeli universities, to the connection to Diaspora, and to our ability to send doctors to train abroad,” he said.

The Sackler Health and Sciences complex at Tel Aviv University. (screen capture: Google Street View)

The American programs, the oldest of which has been operating for 46 years, have graduated thousands of doctors over the years, many of whom now work in top hospitals and clinics across the United States.

“Those graduates go on to get key positions in American hospitals,” Afek said.

According to Afek, those connections currently make it easier for Israel to send its own doctors for fellowships in those facilities to improve their professional capabilities and thus raise the level of healthcare in Israel.

“So we want to send our doctors to the US, but are refusing to train American doctors here in Israel?” he said.

Afek raised alarms that the closure of the programs would harm Israel’s ties to the American Jewry. Though the programs are open to participants of any faith, because they are in Israel the majority of the students are Jewish.

Students from Ben Gurion University of the Negev’s Medical School for International Health (MSIH) Class of 2019 at Soroka Medical Center. (Courtesy)

Nonetheless, the move has been backed by Diaspora Affairs Minister Nachman Shai.

The closures will “increase the amount of seats available for Israeli citizens in medical schools, instead of giving them no choice but to study abroad and perhaps not returning back home,” he told The Times of Israel.

Affect rejected Shai’s view, maintaining that foreign and Israeli students need not be in competition; keeping the American programs open and allowing more Israeli students to study medicine were not mutually exclusive.

“These programs are an important connection with Jews of the Diaspora,” he said. “We can’t just keep hurting those connections over and over again.”